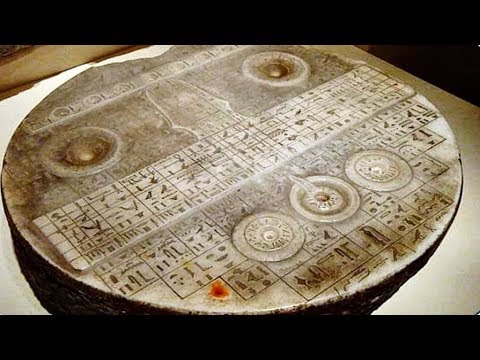

Decoding the Antikythera Mechanism

A Greek shipwreck holds the remains of an intricate bronze machine that turns out to be the world's first computer.

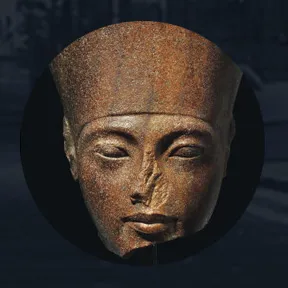

In 1900, a storm blew a boatload of sponge divers off course and forced them to take shelter by the tiny Mediterranean island of Antikythera. Diving the next day, they discovered a 2,000 year-old Greek shipwreck. Among the ship's cargo they hauled up was an unimpressive green lump of corroded bronze.

Rusted remnants of gear wheels could be seen on its surface, suggesting some kind of intricate mechanism.

The first X-ray studies confirmed that idea, but how it worked and what it was for puzzled scientists for decades. Recently, hi-tech imaging has revealed the extraordinary truth: this unique clockwork machine was the world's first computer.

An array of 30 intricate bronze gear wheels, originally housed in a shoebox-size wooden case, was designed to predict the dates of lunar and solar eclipses, track the Moon's subtle motions through the sky, and calculate the dates of significant events such as the Olympic Games.

No device of comparable technological sophistication is known from anywhere in the world for at least another 1,000 years. So who was the genius inventor behind it?

And what happened to the advanced astronomical and engineering knowledge of its makers? NOVA follows the ingenious sleuthing that finally decoded the truth behind the amazing ancient Greek computer.

The Antikythera mechanism was designed to predict movements of the sun, moon and planets.

The artifact was recovered probably in July 1901 from the Antikythera shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera.

Believed to have been designed and constructed by Greek scientists, the instrument has been dated either between 150 and 100 BC, or, according to a more recent view, in 205 BC.

After the knowledge of this technology was lost at some point in antiquity, technological artefacts approaching its complexity and workmanship did not appear again until the development of mechanical astronomical clocks in Europe in the fourteenth century.

All known fragments of the Antikythera mechanism are kept at the National Archaeological Museum, in Athens, along with a number of artistic reconstructions of how the mechanism may have looked.

Generally referred to as the first known analogue computer, the quality and complexity of the mechanism's manufacture suggests it has undiscovered predecessors made during the Hellenistic period. Its construction relied upon theories of astronomy and mathematics developed by Greek astronomers, and is estimated to have been created around the late second century BC.

In 1974, Derek de Solla Price concluded from gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces that it was made about 87 BC and lost only a few years later.

Jacques Cousteau and associates visited the wreck in 1976 and recovered coins dated to between 76 and 67 BC.

Though its advanced state of corrosion has made it impossible to perform an accurate compositional analysis, it is believed the device was made of a low-tin bronze alloy (of approximately 95% copper, 5% tin).

All its instructions are written in Koine Greek, and the consensus among scholars is that the mechanism was made in the Greek-speaking world.